Front Line Fashion: How The Military Influenced The Way Men Dress

Blame Louis XIV. There he was minding his stately business when he met some Croatian mercenaries working for the French Army during the Thirty Years War. They wore boldly patterned strips of fabric around their necks, ostensibly as a means of signalling their comradeship. But Louis rather took to the idea himself and, being king, what he wore was fashion. The cravat – and later the tie – was born.

Pity the pacifist – he has nothing to wear. Look over the male wardrobe and there are few civilian garments that did not go through military boot camp first. Or the officer’s mess for the more sophisticated items Practical and durable, military clothing speaks to the utilitarian in all of us. It works. It lasts. And, yes, it looks good, too. Today, military recruits proudly serve not just on the home front, but at work and in play.

German armed forces wearing khaki uniform

Anything typically khaki-coloured you’d expect to have such a start in life. Like khakis, for example: ‘khaki’ coming from the urdu for ‘dun-coloured’, a more practical alternative to the aptly blood-red uniforms worn by the British Army until the late 19th century. The trouser style, meanwhile, often called chinos, come from the loose-fitting Chinese-made trousers worn through the Philippines and adopted by the US Army during the Spanish American War.

Sometimes the clue is in the name: the bomber jacket, for example. Or the trench coat, beloved of noir-ish detectives and a commonplace sight during the coming bad weather. First devised by Aquascutum and Burberry for men of suitable wealth and rank – not the lowly grunts – it was designed to protect them from the mud and guts of the World War I dug-outs from which it takes its name. It has even retained certain distinctive characteristics long after their original use has faded away. We assume you don’t needs the storm flap on the shoulder to soften the recoil of one’s rifle, for example.

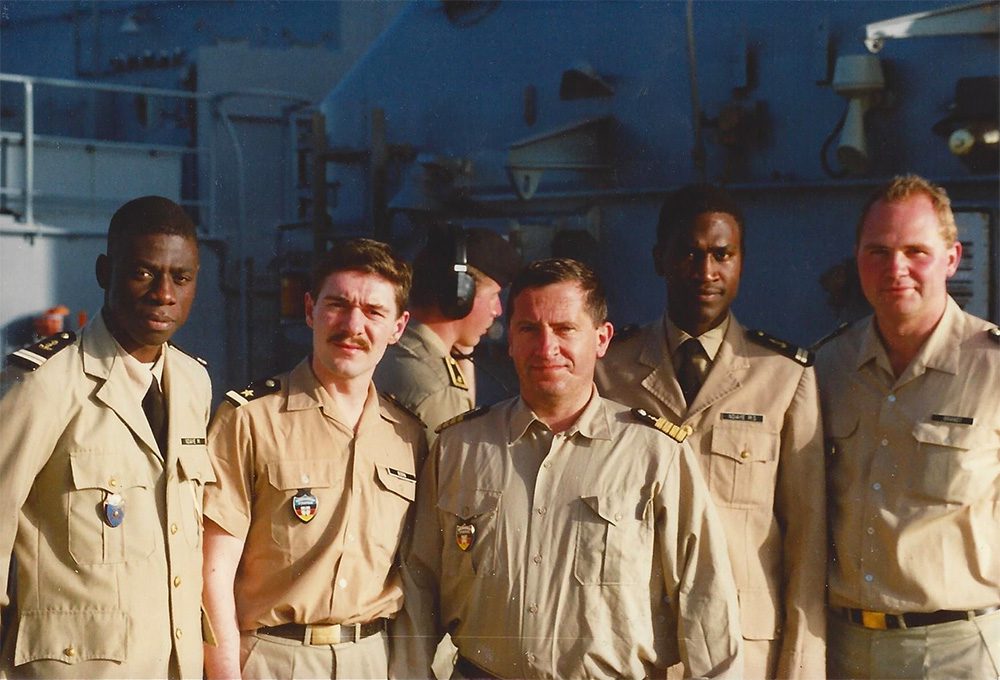

Men In Uniform

Elvis in full military uniform during his enlistment

Even that most peacetime of garb, the tailored suit jacket, is a descendant of the frock coat, which by turns had its origins in cavalry officers’ uniform. Indeed, the most innocuous of clothing items have military beginnings. The belt also comes from 19th century Prussian cavalry officers’ uniforms. The cotton T-shirt, made standard issue kit for the US Army, derived from an amalgam of the short-sleeved woollen underwear worn by most British men of the early 20th century, and the long-sleeved cotton Union Suit-style underwear worn in the US.

The peacoat – check. The blazer – check. The blucher boot – check. Wellington boots – you may have heard of Waterloo. Combat pants – surely no surprises there. Aviator sunglasses – again, it says so on the tin.

Even clothes that, frankly, you don’t wear that often – the balaclava, the kilt, perhaps the cardigan – all have military origins. In fact, if it didn’t originate in sport, that other great wellspring of menswear classics, there are few staples of the modern male wardrobe that didn’t come from the army, navy or air force. And even if it did originate in sport, there’s a chance it actually properly originated in the military. The baseball jacket, for example, was derived from the US Army’s WW2 Winter Combat Jacket.

Many of menswear iconic pieces started life in the military, including the MA-1 bomber jacket

Many military garments haven’t shaped menswear, so much as been lifted wholesale to become a mainstay of it. The MA1 jacket, the M43 field jacket, the M51 parka: all have a proud service record. On the rare occasion that the reverse occurred, and the military embraced a civilian design, it did so with such gusto that its peacetime beginnings have almost been forgotten.

The duffel coat, for instance, was designed in 1890 by Staffordshire-based outfitters John Partridge, also creators of the donkey jacket, in 1869. Field-Marshall Montgomery adopted it, almost as a trademark, in World War II and officers and navalmen followed his lead. But it was the very use by the military that gave these garments charisma.

Fighting Spirit

Perhaps this is not all that surprising. Of course, these military looks live on in part because men’s fashion loves a masculine archetype, and what – traditional thinking goes – could be more macho than a soldier, notwithstanding the sexual overtones afforded a ‘man in uniform’? Then there’s military detailing. An epaulette there, an extra pocket here, a touch of camo all over… These are trends almost any season.

But the influence also lives on for one, simple, overriding reason: military clothing works, and not least because governments could hardly afford for it not to. Today, as in the run up to World War II, the R&D spend for US military uniform dwarfs even the wildest imaginings of any designer brand. It’s that gargantuan spending that also means there’s so much surplus.

Today, military is a huge streetwear influence

That has allowed youth and streetwear subcultures to see value in military clothing being not just affordable, but readily customised. There’s also political commentary in subverting, or in some instances exacerbating, the military origins. Peace protesters, punks, clubbers, break-dancers, Black Panthers and Neo-Nazis alike have worn combat trousers.

Such big spending by defence contractors doesn’t mean they always gets it right. A camo of various shades of blue and grey developed for the US Navy was phased out from 2016 after only a couple of years in service once it was acknowledged grimly that it was useful only if you wanted to hide while being lost at sea.

Nor should this suggest that the military’s crossover into fashion is a new thing. The Roundhead style of the English Civil War (1642-51), adopted initially as a poor means of distinguishing them from enemy Cavaliers, brought about a simplification of civilian dress after the conflict. Years later the adoption of shoulder straps, as a mark of officer rank, went mainstream. A hat brim turned up to facilitate firing became the popular cocked hat…

The military has access to the toughest, most advanced, most functional fabrics, to ways of testing the ideal pocket size and placement, to means of perfecting the fit or reinforcing stress points. Being rationalist in design – rather than commercial – means military designs have a strength and clarity to them.

And that’s something men tend to admire in so many things. It’s often what gives those things a certain cool. Like our tools, gadgets, cars, wrist watches – another military idea – and all other things that make men feel more like men, we like clothes that work. Sartorially-speaking, we’re all in the army now.