A Brief History of Denim: Menswear’s Most Iconic Material

To most people Kurabo, Nisshinbo, Kuroki and Kaihara are exotic-sounding but largely meaningless words. To these same people, a pair of jeans is likely to be a nondescript, commodity product – something to do the gardening in or wear down the pub. But then, on the flip side, there are others who will recognise these as the names of the four main mills producing denim in Japan, arguably home to the world’s best denim.

Denim being weaved at the acclaimed Kuroki mill, Japan

And these mills are certainly busy. As farfetched as the idea would have sounded just 20 years ago, denim is now an artisan fabric, with top-spec jeans being handmade by lone makers at their workbench. It’s no romantic exaggeration, either. Among this new wave of elite denim makers are literal one-man-band operations, like the individuals behind American labels Roy and White Horse Trading Co, using homegrown denim from Cone Mills, the last of the US’ pioneering mills, or (more likely) one of the many varieties of Japanese denim available.

Cone Mills, the last of the US’ pioneering mills

This is the hallowed stuff which, since the early 1990s, has been arduously woven in Japan on old-fashioned, rattling shuttle looms, repeatedly hand-dyed using laborious loop-dyeing techniques to create the subtle irregularities of texture and fading in the colour – as well as spawning a whole dictionary’s worth of terminology, from “honeycombs” to “whiskers” – that denimheads so love.

These are the jeans with that tell-tale selvedge stripe running along the inside of the outer leg seam (often shown off by the wearer using a turn-up or pinroll). Contrary to popular opinion, this selvedge edge does not necessarily make for a better pair of jeans, more a rarer pair – as not all manufacturers have the looms to weave with a selvedge. These are also the type of jeans that will likely set you back upwards of £250 a pair.

The tell-tale selvedge stripe running along the inside of the outer leg seam

That price point would make your old-time western cowboy wince. He’s the type for whom the classic cut of jeans, known as the “five pocket western”, was designed for – by German-born US immigrant Levi Strauss and Ben Davis. The former took a hardwearing, centuries-old fabric devised in France (“denim” comes from the word “de Nimes”) and popularised in Italy (“jean” comes from the word “Genoan“) and saw potential for it being worn by pioneers, miners and goldpanners. The latter actually came up with the idea of riveting at the stress points and then, lacking foresight, sold the patent to Strauss.

Levi Strauss was a German-American businessman who founded the first company to manufacture blue jeans, in 1847 in San Francisco, California

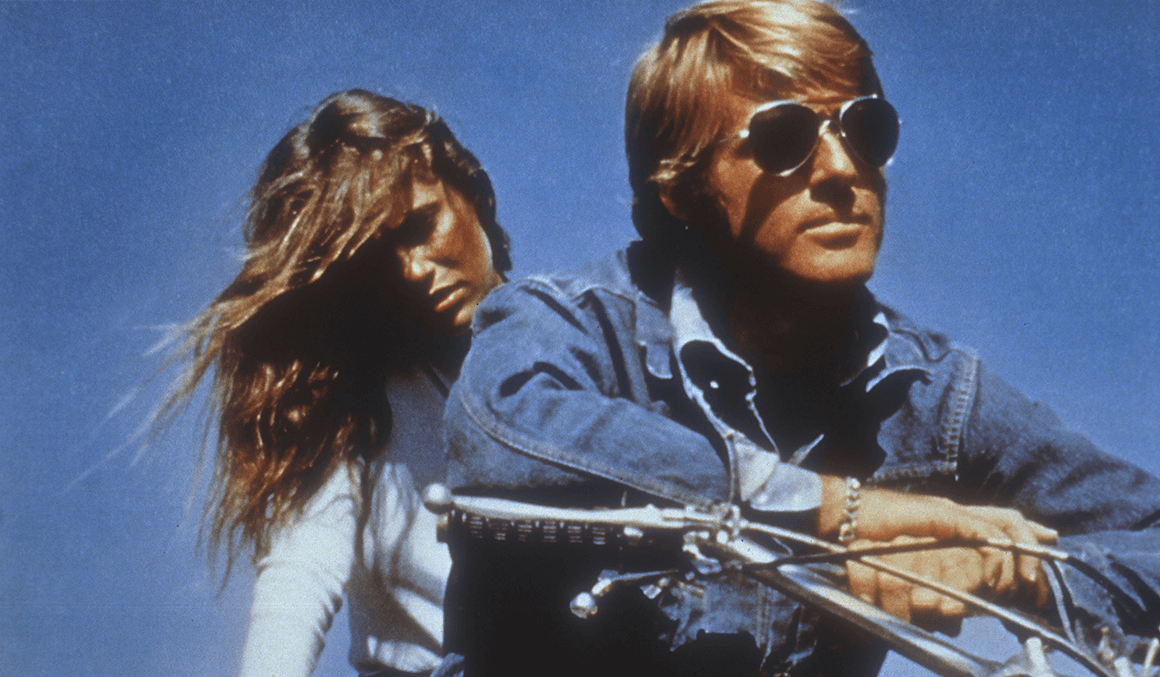

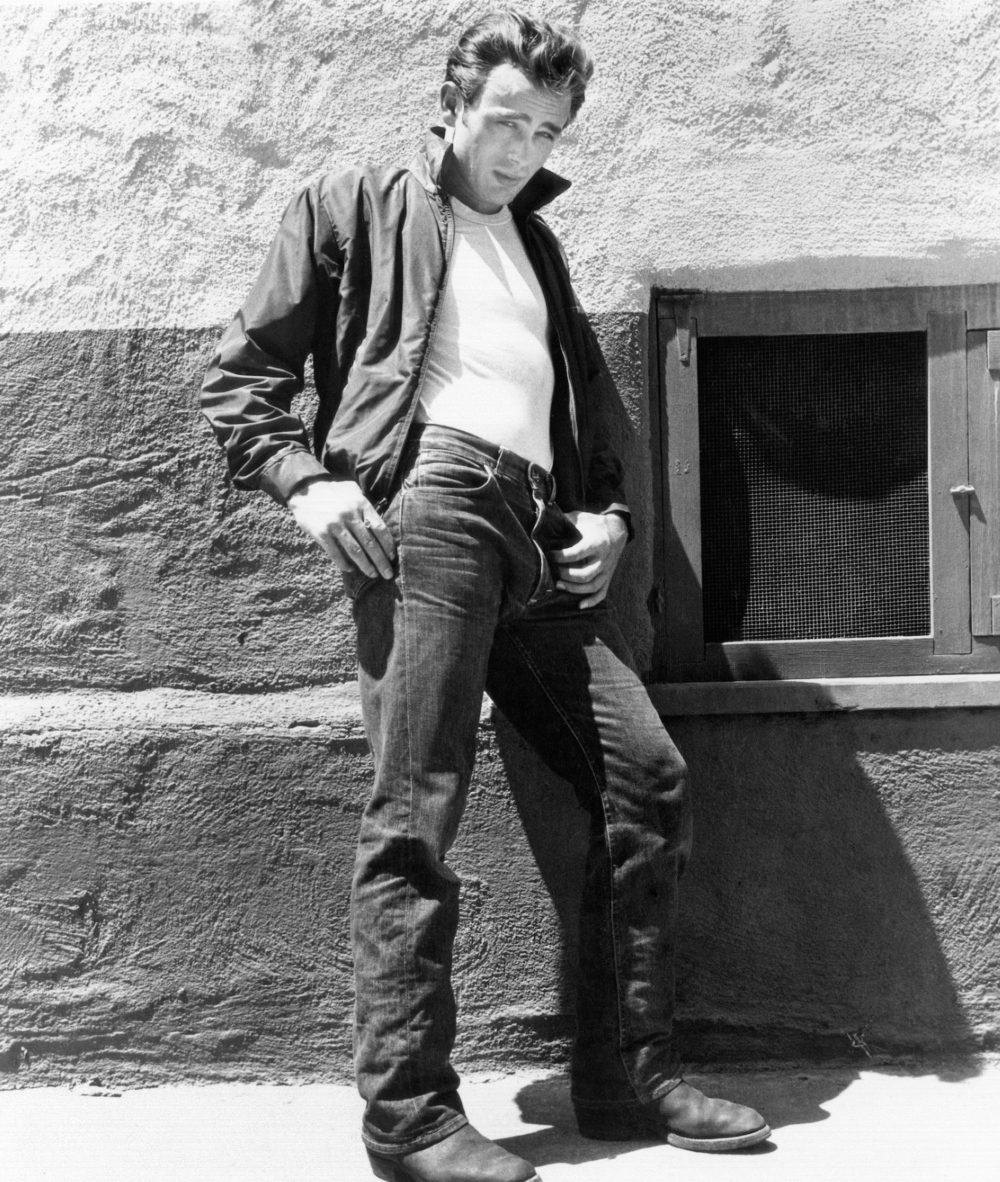

Your old-time cowboy type is used to $15 pairs too, because for most of their history jeans were strictly work clothes, and hard manual work clothes at that, shunned by the finer establishments. The 1950s, after all, had seen the birth of the teenager, and the cinematic rebel – all of whom would be clad in denim. When, in 1951, a hotel refused Bing Crosby entry because he was wearing jeans, he returned later in a suit… made of denim. It let him in.

During the 1950s James Dean made denim iconic in the film Rebel Without a Cause.

That Japan should be the source of the best take on what is a quintessentially American product may seem unlikely. But strangely, in Japan, World War II gave rise not to some desire to embrace a more homegrown look, but that of the occupying forces. It spawned a youth cult for all things Americana and, a few decades later, a fledgling Japanese fashion industry seeking to recreate American raw blue jeans better than the Americans.

There is a romance to the products which come out of Japan. But there’s also an insane attention to detail, often copied direct from world-class vintage denim collections. It’s this, more than anything, which has created a market for connoisseur denimheads.

Demim looms at Kaihara mill in Japan

It was a company called Big John, which had been a textiles and uniform manufacturer, that became the first domestic denim brand in 1965. Edwin has a similarly long history. And they have since been joined by a growing plethora of ever-more esoteric makers, such as Sugar Cane, Momotaro and Real McCoys, as well as the pioneering so-called “Osaka Five”: Full Count, Evisu, Warehouse, Studio D’Artisan and Denime. The list of makers goes on, including many yet to sell outside of Japan – which, of course, adds to their cachet and desirability.

The iconic Edwin denim jeans tab and logo

Each claims their own specialism, be that the precision with which they remake Levi’s classic styles of the 1930s to 1950s, or the use of natural indigo dyes, or the emphasis on heavy and super-heavyweight denims – perhaps 21 or 25oz as opposed a more typical 12 or 14oz, this itself being sturdy stuff compared to the positively flimsy 8 or 9oz mass-market denim you will find on your local high street.

Yet while the Japanese mills and makers may dominate the artisan market, they are no longer alone. Even the Swedes – Nudie, Pace and Neuw, amongst others – are becoming renowned for their denim now.

A vintage Gul & Bla denim advert, date unknown

Don’t scoff. Sweden has a denim culture dating back half a century. It was then, in 1966, that the pioneering brand Gul & Bla was formed by Lars and Maria Knutsson, sparking a jeans explosion for a youth market unable to buy Levi’s or Lee, then still a rarity outside of the US. The company was at the forefront of development of the techniques to allow aged washes and other treatments, a science that has since largely been taken on, and over, by Italian “laundries” (as the factories that develop and produce pre-distressed effects are known). The point? Denim has become a global culture – Indonesia and Turkey have recently become hot spots, for example.

David Beckham wearing double denim in a Tudor Watches advert

Is it all a bit crazy? Of course it is. Jeans have, in the 21st century, become a foundation garment for the way we dress on a daily basis – which is incredible in itself, given that the style is, in effect, largely unchanged since the 1890s. They’re durable, comfortable, age beautifully, can be worn with anything and, given a recent relaxation in dress codes, almost anywhere. Jeans are the single best-selling garment in history. They’re also utterly utilitarian, in a good way: a basic pair of jeans – and there’s barely a menswear brand that doesn’t offer a pair now – will serve much the same purpose as a much more expensive version.

It’s all these factors, plus others – their heritage, details, culture and craft – that make denim and jeans an unusually rich subject among all clothing stories, and which have encouraged the obsessives to obsess. And you know what? They’re onto something.